I’ve recently been trying to make sense of ‘acceptance,’ both the word and the underlying concept. It started to make more sense to me when I realized that the word acceptance refers not to one concept but to three (at least) that can roughly be seen as building on one another, that is, the latter concepts of acceptance require the achievement of the lower concepts. So, I now understand acceptance more like a journey with three stops. Depending on a person’s emotional responses and needs and life circumstances, they can get on or off at any stop. I present the following for your consideration and feedback. I think you’ll see the clinical applications

Acceptance 1: Acknowledgement: Recognizing the state of affairs that one finds oneself in, including of one’s emotions, place in the world, past experiences, or expectations of the future. This recognition occurs irrespective of one’s estimation of these states of affairs, whether perceived as good or bad, good or evil, or desired or undesired. Opposite of Acceptance 1: Denial.

Acceptance 2: Accommodation: Having come to terms, emotionally and practically, with what one has acknowledged. Abiding and achieving tolerance of one’s self, others, and the state of the world. Opposite of Acceptance 2: Rejection

Acceptance 3: Affirmation: Approving of or embracing what one has accommodated to. May include a sense of celebration, pride, gratitude. Opposite of Acceptance 3: Shame

Let me share two examples.

Miriam

Miriam is a mother of two children, in first and third grades. She is a Ph.D. biologist with her own lab at a top-ranking university, has grant funding, and recently achieved tenure. Despite her markers of success Miriam has been feeling increasingly depressed, tense, and angry. When asked to describe these feelings, Miriam goes on at length at how “everyone slows [her] down” and admits to being “short and curt” with people. She complains about her husband, kids, and co-workers. When pressed to explore the source of her frustrations, she says she loves doing the work of a biologist, feels she is making genuine breakthroughs in her field and wishes she could spend more time in the lab, where she says she feels she “belongs.” She pauses and looks distraught and says she realizes that she experiences the rest of her life as a hindrance to doing her beloved lab work. When asked why this is a distressing realization, she says she just realized she doesn’t like being a mother “all that much.” She tears up and says she must be a horrible person, that she feels overwhelmed with this realization, and just can’t talk about it anymore. She leaves.

Six months later Miriam is back. She reports she went through an emotional rollercoaster following her realization about “not being thrilled with motherhood.” After weeks of soul-searching she accepted that, “#1 I am who I am and can’t change what is most important to me and #2 my kids deserve a loving mother.” For several more weeks, Miriam struggled trying to “square the circle” between these competing goods. Finally, a vision began to fall in place. She consciously and with intention became more patient and emotionally available to her kids and husband, cut down on “some of the grunt work of parenthood” by getting a part-time helper for doing household chores and driving the kids around, requested additional help from her husband who complied, and reviewed how she spends time at work. “After all,” she said, “not everything a person does is of equal value.” She identified where she spends time unproductively at work, where she can outsource some of it to her post-docs, and to what she can say No.

She says in hindsight she is happier, less stressed for time, more patient with others and herself, and more accepting of herself as a person and in her life roles. It feels good, she says, to be able to see herself and the world the way they really are and “not have to pretend otherwise.” This, she says, allowed needed changes to have taken place.

Victor

Victor is a man in his late 20s with a history of depression, alcohol abuse, failed relationships, and needy and psychologically abusive behaviors. Victor speaks at length about his relationships, how he starts out feeling optimistic that “this person is finally the one” only to be again disappointed and “betrayed.” At one point in the conversation, he says he feels like a volcano that can “blow at any time.” When asked if he remembers when he first started feeling this way, he says he knows exactly when, where, and why. He says he’s reluctant to talk about it, but it has to do with being sexually molested by a coach when he was 14. He says that maybe next time he can say more about this experience.

When Victor returns, he says he still doesn’t want to talk about being molested. When asked if he could instead focus on the consequences of this event for his life rather than the event itself, he says he can try. He goes on to describe how angry he is “like all the time” because he can’t get over the thought of “what my life would’ve been like if that thing didn’t happen” and that he “just can’t let go of this thought.” He is reassured that this is a common reaction and that it is hard to let go of comparing the bad that happened with what life without that bad thing happening would have been like, that the first step is to acknowledge that he has suffered, lost out on what might have been and should have been, and how deeply unfair this was. Victor nods his head and says he needs to think about all of this because it’s making his head spin.

Victor doesn’t return for three months. When he does, he says that over this time he’s been “the most emotional” he’s ever been, that he’s been “crying and yelling when driving and isolating and feeling a lot of things.” But he’s says it “feels good somehow.” He started attending church services and struck up a friendship with a pastoral counselor there who helps him by “just being there and listening to me rage and not judging me.” He says he’s grieving for the boy he was before being molested because “that boy died that day.” He tears up and smiles at the same. He says this is far from over, but he has more hope he’ll get through this. He says he finds himself thinking he should become a counselor himself since his experience gives him the understanding “to help other kids who’ve maybe been abused.”

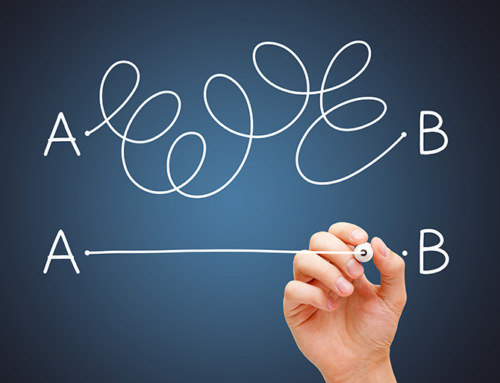

In conclusion: having written down what I just wrote I think that acceptance in all its ways is less like a train route with three stops and more like a circular path, in which each time around a little bit more of the different forms of acceptance come onboard. For some, this journey will last a lifetime.

Until next time,

Dr. Jack

LanguageBrief

Today’s Quotes

“You couldn’t relive your life, skipping the awful parts, without losing what made it worthwhile. You had to accept it as a whole – like the world, or the person you loved.”

Stewart O’Nan“Life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don’t resist them; that only creates sorrow. Let reality be reality. Let things flow naturally forward in whatever way they like.”

Lao Tzu“To be fully seen by somebody, then, and be loved anyhow – this is a human offering that can border on miraculous.”

Elizabeth Gilbert“Real isn’t how you are made,’ said the Skin Horse. ‘It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.’ ‘Does it hurt?’ asked the Rabbit. ‘Sometimes,’ said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. ‘When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

Margery Williams Bianco“I have never found anybody who could stand to accept the daily demonstrative love I feel in me, and give back as good as I give.”

Sylvia Plath

Leave A Comment