Earlier this year I shared a post on ways of increasing and maintaining motivation to achieve success in relevant life projects. I pointed out that there were two categories of motivational strategies, internal and external ones. Today, I expand on a type of external one because, as I wrote previously, the external category of strategy is underused, in my experience. First, here is a definition of the categories from that post.

- Internal Strategies: strategies that directly focus on altering one’s mental states, such as thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and objects of attention.

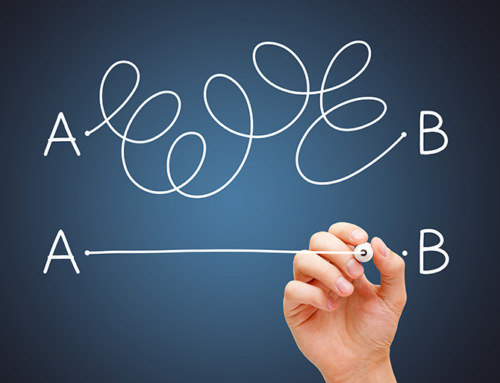

- External Strategies: strategies that directly focus on altering environmental conditions to shape one’s behaviors. In effect, a person changes their environment that then ‘coerces’ them to maintain their commitments over the long haul.

When I started API (then called Blue Tower Institute) in 2002, my dominant success strategy was an external one that I now call Assured Success. Back then, after working for a competing company that I believed was “doing it all wrong,” I decided to start my own psychiatry oral board prep courses. This part was easy because it entailed simply telling myself I would do it. The next part was hard – very, very hard – and it began when I placed ads in a psychiatric newspaper and sent postcards to prospective customers. It was at this point that my internal desire, decision, and sense of motivation took on a life in the wider world. My project became even more real when colleagues preparing for their boards signed up.

In foolhardy fashion, I had committed to holding a 5-day course within three months from my initial decision. And those three months began before any tasks were started, let alone completed. I was so very stressed over those three months that I lost 15lbs from not eating enough and I regularly woke up at 5am with my heart racing and a distinct voice in my head saying, “Who the hell do you think you are?” Clearly, my inner voice did not have confidence in me. The only reason I went through with that course as planned is that I realized that if I canceled it, I would cause more harm to the psychiatrists who had already registered than if I went ahead with the course, even if it wasn’t perfect. I felt trapped and trudged forward as best I could. And, btw, that first course was pretty good although not nearly as good as the ones that followed.

So, I trapped myself in my success. I went on because I had to go on. The only way out was through holding the course.

I did all this not because of insight into the workings of my mind or anyone else’s. Instead, I blundered into a strategy that turned out to be among the most successful ones a person can use. I set up external conditions that forced me to do what I had set out to do. The caution is, of course, not to act in ways that expose oneself or others to real hazards. For instance, I would not recommend committing to climbing Mt. Everest in three months unless one is already an experienced climber in nearly top form.

Here are some more quotidian examples of how to set conditions for success.

- If you wish to succeed in regularly working out at the gym, you can partner with a friend and set times for driving there. You can take turns driving there and commit to preset days and times. You are much more likely to get in your car to pick up your friend or get in your friend’s car who comes to pick you up than you would to drive there on your own.

- Set a date for a running or cycling race that is outside your current capacities to complete but, with adequate training, is achievable. Partner with one or more people and engage in mutual training. Everyone in the group commits to regular attendance in training sessions, barring rare misses due to unavoidable conflicts.

- Whatever you wish to achieve you can box yourself in by announcing it to everyone you know. This adds inspiration and the fear of embarrassment if you don’t carry through on your loudly announced project. If you want to take it to another level, you can schedule a celebratory party at some future day and invite everyone to celebrate the success you will have achieved by that time. If you lose 15 lbs in the meantime, oh well. Maybe that’s a good thing. Examples of life projects to celebrate include recording your first musical CD, finishing your novel, starting a business, or retiring.

Once you have set, committed to (internally), and boxed yourself in (externally) to your goal, you must plan it out. Of course, having a preliminary plan before setting the deadline for your success is needed to choose a reasonable date. But, after that date is set, more detailed planning and monitoring of progress will need to occur. With this impossible-to-ignore date for launch, you will use every available minute to complete the required work or training. Parkinson’s Law is operative here: work always fills the allotted time, that is, the amount of work required adjusts to the time available for its completion. The eponymous Parkinson here is Cyril Northcote Parkinson who coined the term in 1955 in an article he wrote in the Economist magazine.

So, what will likely happen is that you will develop an elaborate plan or overly ambitious outcome at the start. As your remaining time dwindles, you will be faced with scaling back the plan and the planned output. This will likely happen multiple times. You will beat yourself up and feel embarrassed ahead of time about how inadequate the finished product will be. But one thing is certain – or it must be maintained with iron resolve – that the show will go on as scheduled. Usually, but not always, it will be good enough. Sometimes it won’t be. But almost always you will be much further ahead than you would otherwise be.

Of course, you might think that I am simply expending a lot of words on saying that deadlines work, so use them. In one way that’s all I’m saying. But there is an extra bit to it. When we were in school, we had deadlines imposed on us. Now, when we set out to fulfill a life project that no outside power is coercing us to complete, that changes the situation. We still can set deadlines for ourselves, but if they do not have consequences, they are unlikely to hold. And, after all, no one else cares if you record and release your CD, climb some mountain, write a book, or run some race – other than you. So, if you are both the worker and the taskmaster, that will often not be enough to force doing the hard work that is required. The worker part of you will whine to the taskmaster part of you about the amount and difficulty of the work required, about how busy you are with other more urgent projects and responsibilities, and, after all, why the rush anyway. And the taskmaster part of you, who is equally overworked and unhappy with this commitment that your past self made, will absolve you of the work. Then both parts will be relieved and promise to cover for each other about why the work remains undone.

Good luck to you and you and you and me, as we each struggle to do the hard work that needs to be done to succeed at that which is most dear to us.

Thanks,

Dr. Jack

Language Brief

“Do not whine … do not complain. Work harder. Spend more time alone.” – Joan Dideon

“Take up one idea, make that one idea your life. Think of it, dream of it, live on that idea. Let the brain, muscles, nerves, every part of your body be full of that idea, and just leave every other idea alone. This is the way to success.” – Swami Vivekananda

“Too many irons, not enough fire.” – S. Kelley Harrell

“I don’t care what you think about me. I don’t think about you at all.” – Coco Chanel

Leave A Comment