Burnout is “a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job,”1 stressors that are often experienced as emotionally demanding. Burnout is characterized by the triad of 1) emotional exhaustion, 2) feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and 3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.2 These core burnout symptoms lead to serious job and interpersonal disruptions, including increased rates of absenteeism, intention to leave the job, medical errors, and marital stress.3 Burnout is highly prevalent among physicians, with prevalence rates estimated to be 50% or even higher.4 Mental health clinicians have not been spared.5,6

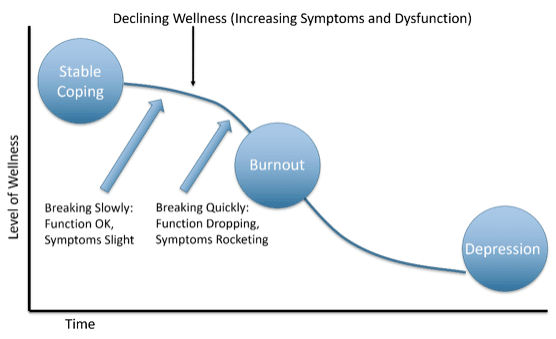

Today, I present ideas on how burnout can be avoided or, if a clinician already suffers from it, how to recover from it. I start with an illustration of the relationship among stable coping, burnout, and depression.

Burnout’s Relationship to Stable Coping and Depression

As the above image illustrates, burnout can be conceptualized as a condition between stable coping and development of a psychiatric disorder such as a depression or anxiety disorder. The curved descending line represents declining wellness characterized by increasing symptoms and dysfunction. It also illustrates that there are no hard boundaries either between stable coping and burnout or between burnout and depression. The ‘S’ shape of the line represents a slow, gradual decline of wellness which accelerates in the course of the descent into burnout and a possible psychiatric disorder. A character in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises was asked how he went bankrupt. He answers, “Gradually, then suddenly.” This dynamic of slow onset then fast decline is common in the development of burnout and many psychiatric conditions, as I’ll discuss shortly.

Burnout is not a unitary condition. Individuals with burnout can present with different profiles, some primarily experiencing depressive symptoms while others anxiety symptoms, while for others still, behavioral and neurovegetative symptoms may be most prominent.3 Also, as illustrated, burnout is not a stable condition, but one that often worsens over time. Additionally, although burnout often presents with depressive and anxiety symptoms, there is evidence that it is distinct from a mental disorder, in particular from depressive or anxiety disorders. Instead, burnout is an “occupationally-specific dysphoria” and behavioral syndrome.3,7 Despite evidence of its separation from depression and anxiety disorders, it is a risk factor for both of them.

The ways that burnout may differ from depression and anxiety disorders are in its scope of disruption and in the self-sustaining nature of that disruption. Burnout may be limited to work times or, more broadly, to workdays. When a person experiences relief and an increase of wellness on weekends and during vacation, that indicates that the disruptions have neither spilled into all life spheres nor that they are self-sustaining. Depression and anxiety disorders, like many psychiatric disorders, become self-sustaining, that is, they become a new normal with each area of disrupted function, such as sleep disturbance, loss of energy and initiative, dysphoric mood, trouble concentrating and deciding, reinforce each other in a dynamical way. This means that each effect of an initial symptom circles back to cause further increase in that symptom as well as causing additional symptoms. In effect, a series of vicious cycles occur leading to a new homeostatic state, one that is hard to disrupt.

Given this, the question is how can a person intervene, make necessary changes, as early in the process as possible. The problem is that the start of the decline of wellness starts gradually, to the degree that function is almost normal. Thus, there does not appear reason for worry or for intervention. After all, sometimes work and other life stressors increase. This is part of the ebb and flow of normal life. So, slight declines in wellness/function are usually normal and to be expected, but sometimes they are harbingers of something worse to come. How to differentiate? Here I introduce the concept of resilience that can help differentiate normal fluctuations in the state of wellness from the beginning stages of burnout.

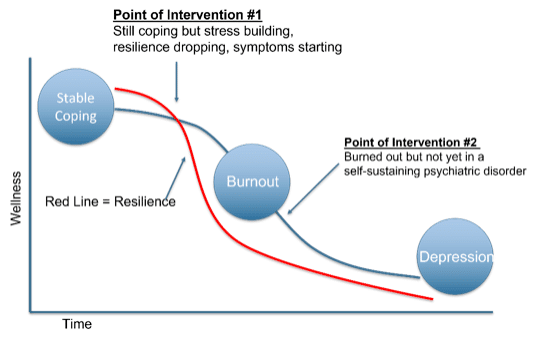

The illustration below adds two concepts that I will cover in the next two sections: resilience and points of intervention.

Resilience

Each person coping stably has an individual overall level of resiliency and specific types of resiliencies. Overall resiliency depends on temperamental factors, strength and breadth of coping strategies, level of competency in fulfilling work roles, and strength and breadth of support systems. A person with high general resiliency can cope with myriad stressors and with higher levels of combined stress severity. Within a person’s overall resiliency, they have a range of specific susceptibilities and resiliencies. Overall resilience is important in recognizing the transition into burnout, while specific resiliencies are important in choosing interventions.

In terms of recognizing the onset of burnout, let’s focus on overall resilience. I’ll define resilience as the capacity to maintain health and wellbeing in the face of myriad stressors. The second image above now includes a curved and descending red line. This line represents level of resilience. I regard it as a ‘leading indicator,’ that is, a change that occurs early in a process of change that heralds or predicts associated changes. Thus, focusing on a person’s level of resilience can help earlier identify the process of declining into burnout. In my illustration, at baseline, a person evidences stable coping and high resilience. In the face of stressors, a person’s resilience (through all the capacities that contribute to it) is able to maintain that person’s level of stable coping while at the same time becoming depleted. How does one recognize decreasing resiliency? I think the easiest way is to subjectively track it. Most of us can know when we are becoming depleted, ‘barely hanging in there,’ while continuing to function well. One can also say that function is a ‘lagging indicator.’ It declines only when resiliency has become depleted and the capacity to function well falls apart. This brings me to the points of intervention.

Points of Intervention

Point of Intervention #1 is the optimal place to intervene, that is, when the person is prior to burnout. This requires attending to, perceiving, and acting upon signs of stress and depleting resiliency in handling it. Although function remains intact to a large extent and symptoms of burnout are slight, there are telltale signs that resiliency reserves are depleting. What are these signs of depleting resiliency? Again, most people, if they pay attention, will be able to have a gestalt sense that they are ‘running low.’ Signs can include irritability, lack of interest or boredom, thinking about vacation or switching jobs, wasting (more) time on social media instead of doing one’s work, perhaps drinking more, having increased worry thoughts, or problems falling asleep. Each of these signs can be subtle, but when they are perceived together it becomes clear to that person, and perhaps to others, that something is wrong. This is the time to intervene. Interventions should first identify which parts of work or life in general are most stress-inducing and which specific resiliencies are running lowest.

Point of Intervention #2 is intervening when burnout is severe but still short in scope and in its self-sustaining nature from a depressive or anxiety disorder. The problem is that many people working in the medical field are apt to minimize their own distress. Mental health problems are problems ‘other people’ have. The first step is for every health professional to accept the fact that despite their fancy degree and years of experience, they can suffer from behavioral and emotional problems just like the normies. Second, this is where colleagues should empower themselves to intervene when they see a colleague in distress. It can be done subtly and from a place of concern, but it’s better done than not done.

I will end here for today. I look forward to your comments and will circle back in future posts with more on burnout.

Thanks,

Dr. Jack

Language Brief

“Burnout is a slow, insidious experience. Burnout is not afraid of playing the long game. To prevent burnout, we need to play a long game, too.” ― Sally Clarke

“We’re totally guilty of doing too much at once, all while trying to manage the noise in our heads that says we’re not doing enough.” ― Vanessa Autrey

“If you think you can outsmart burnout, burnout will prove you wrong.” ― Sally Clarke

References

- Maslach, Christina. “Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention.” Current directions in psychological science 12.5 (2003): 189-192.

- Maslach, Christina, Susan E. Jackson, and Michael P. Leiter. Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education, 1997.

- Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. J. Vocation. Behav. 79, 549–562. doi: 10.1016

- West, Colin P., et al. “Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” The Lancet 388.10057 (2016): 2272-2281.

- Rotstein, Sarah, et al. “Psychiatrist burnout: a meta-analysis of Maslach Burnout Inventory means.” Australasian Psychiatry 27.3 (2019): 249-254.

- Kumar, Shailesh. “Burnout in psychiatrists.” World Psychiatry 6.3 (2007): 186.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422

Leave A Comment